Albert Einstein once said, “Look deep into nature, and then you will understand everything better.” In a more metaphorical way, writer and poet Khalil Gibran proclaimed, “Forget not that the earth delights to feel your bare feet and the winds long to play with your hair.”

While you should probably refrain from doing any field research in bare feet, there is undeniably a peace and understanding that comes from being in nature. Many enjoy just basking in the beauty of the great outdoors without a care in the world, but for those who are more interested in gaining knowledge from their surroundings, field work can be a fascinating and rewarding experience.

If you’re interested in giving this a try and recording your own findings, read on. I have made some pretty interesting discoveries while scouting, which has been good practice, as I plan to become a wildlife biologist when I finish college. In this article, I’ll be covering some of the steps that you should remember when attempting field work, as well as a bit about my own experience.

1. Map Out Your Scouting Area

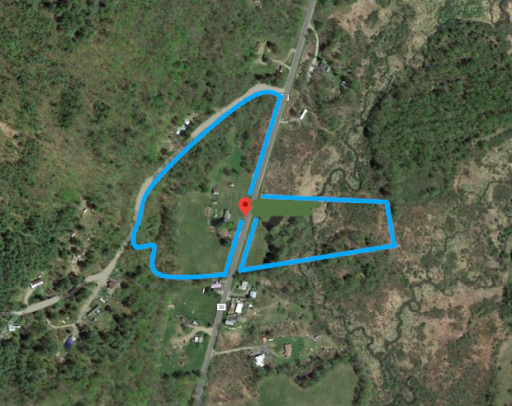

While it might seem unnecessary, it’s good to know exactly where you’re going to be scouting on any given day. For my most recent field work project, I created a satellite image outlining my family’s property and then overlaid a grid to divide the daily sections. I didn’t always complete the full assigned section in a given day, and other times I did extra. It was mostly a guideline for myself to make sure I got enough done within the given amount of time.

Here is the outline of my property that I created on paint 3D from a satellite image. The section that’s blurred out is just where I covered up my address.

There isn’t one correct way to do this; you could always just make a note before heading out that says something like “scouting the hill area.” If you’re on a time crunch, more specific notes tend to work better.

2. What Gear to Use

There isn’t a required set of gear that you’ll need to do field work. That being said, there are a few things that will be extremely useful to have if you’re hiking and looking for animal signs / interesting plants (or whatever you’re scouting for).

The first of these is a camera (or phone) and/or a sketchbook. If you do happen to come upon something that you want to document, it’ll be good to have one of these things with you. I recommend something that you can quickly take pictures with to make your work efficient, but if you like sketching, then definitely bring a sketchpad. Whatever works best for you!

Depending on where you’re doing field work, you might want to take into consideration gear such as hiking shoes, a good windbreaker jacket and a hiking pack. If you’re scouting in your backyard, this shouldn’t be much of a concern. If you’re going to a hiking trail or wildlife management center, however, these will be very good to have.

Some other things you might want to bring are containers for collecting any interesting samples you find (I’ll show a few examples of these in the next section) and a notebook for writing down anything that you want to remember for later.

3. The Field Work

When I do field work, I like to use a grid system to make sure that I cover the whole area. Because animal signs such as prints and hair will be so small, they are very easy to miss. This is why you must keep a vigilant eye on the ground, and don’t be afraid to move slowly. One of my best experiences while doing field work was when I found two different types of animal hair/fur on the same hill, and was quickly able to identify them.

The first was a clump of rabbit fur, which I recognized from a rabbit hide that I tanned last year. When I compared it to be sure, I found that it was a perfect match.

The second sample I found was a good amount of thick, wiry white hair, which I identified as being from a whitetail deer. Like with the rabbit fur, I compared it to a hide that matched.

4. Some Possible Findings

Besides prints, droppings and animal hair, there are many other things that you could find while doing field research. You might see a bedding area, a skeleton (a wild animal one, hopefully!), or maybe you’ll come upon a live animal itself. You might also see changes in the environment, such a rising water source. This is something that I observed during my recent project, when I found that my family’s stream had not only risen, but overflowed. The puddle that formed on the side of the bank was surprisingly deep. Here’s a picture of me standing in it with my muck boots on, as well as the stream itself, which would certainly not have been safe to cross!

5. Analyzing Your Data

One of the most fun parts of studying nature and documenting your findings is the part where you have to make sense of them. You can determine what areas are most popular for certain animals, where they most like to drink, where they prefer to eat, and perhaps you can even estimate the population sizes.

If you’re interested in coming up with a male:female ratio for deer in a given area, a great way to judge genders by hoof tracks is by how large and close together the hoof prints are. The males’ hooves tend to be farther apart, and much bigger.

Here is a track from a buck that lives on my family’s property.

6. Contribute to a Citizen Science Project

If you’re interested in doing field work but don’t want to analyze the data, or you like the whole process but want your research to be part of something bigger, consider contributing to a Citizen Science project! Such projects allow anyone, even non-scientists, to gather their own findings and contribute to a wider-scale data collection program. There are many of these out there, and you can find one for your specific interest and location.

While searching for some based in NY (or without a specific region), there were two that I came upon that you might like to check out. The first of these is eMammal (run by Smithsonian), which allows people to share wildlife pictures using their “camera trapping” software. Anyone around the world can take part, and it’s for people of all ages.

The second is Nature’s Notebook, which tracks seasonal nature changes and only requires you to make an account on the site (no payment required). There are lots of subdivisions on the site itself so you can focus on specific types of animals and projects, such as “Pesky Plant Trackers”, “Flowers for Bats”, and over 1400 animals species.

https://www.usanpn.org/natures_notebook

Happy scouting!

Reference: https://parade.com/1034896/marynliles/nature-quotes/

by

by